Dunleavy’s fiscal plan: Sales tax for you, tax cuts for corporations

It's not just a plan to branch the state's finances until the next great oil boom, but a plan to shift the state's tax burden from the well-connected to everyone else.

Good morning, Alaska. It’s Tuesday.

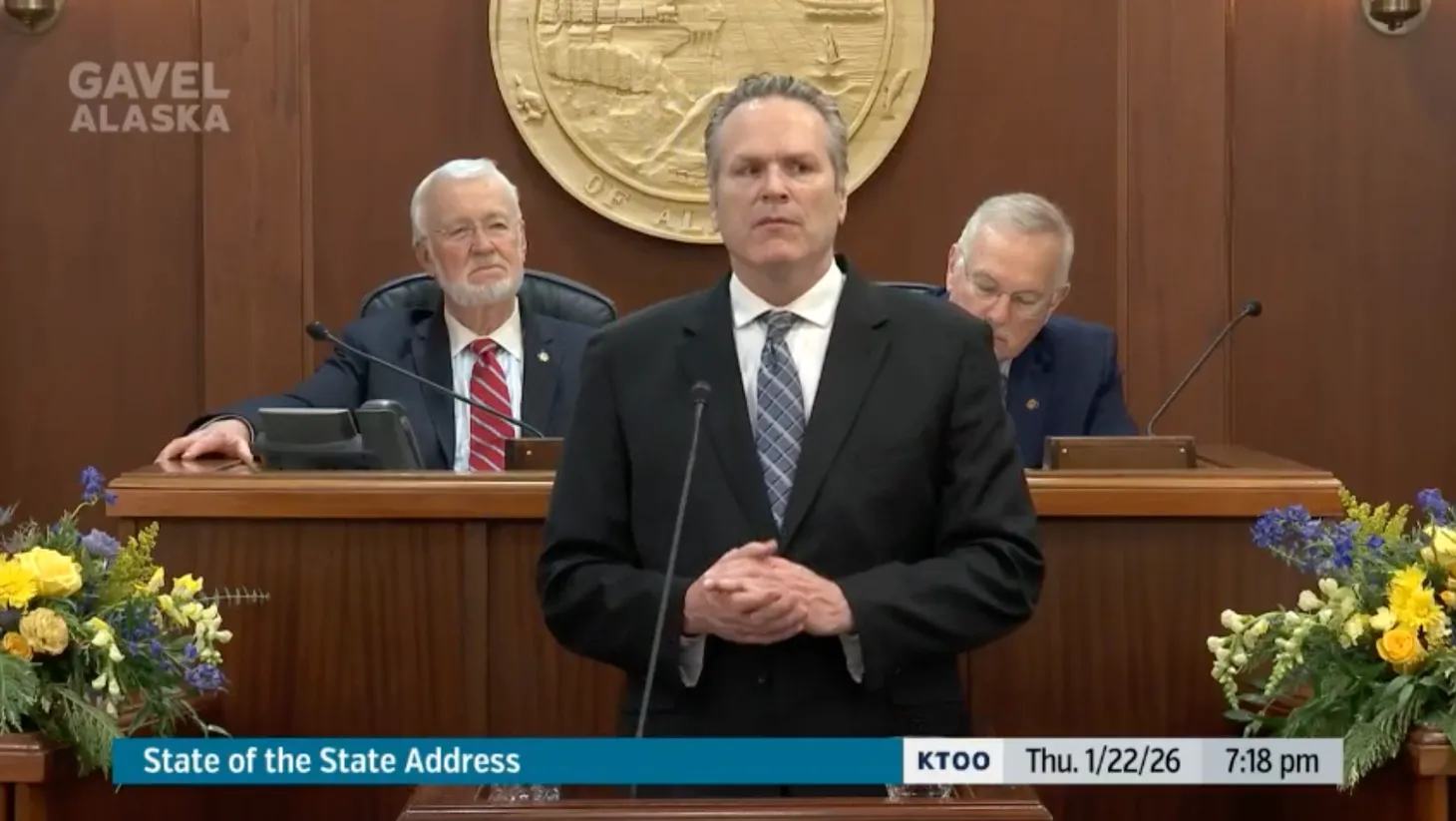

In this edition: Gov. Mike Dunleavy unveiled his omnibus fiscal plan on Monday, combining a deeply regressive sales tax based on one of the country's most regressive states with generous tax cuts for large corporations and other conservative red meat. It's not just a plan to branch the state's finances until the next great oil boom, but a plan to shift the state's tax burden from the well-connected to everyone else.

Current mood: 💵

Dunleavy’s fiscal plan: Sales tax for you, tax cuts for corporations

Gov. Mike Dunleavy’s omnibus tax bill landed with a thud on Monday, outlining a plan that would see everyday Alaskans paying higher taxes than corporations for several years. The “temporary, seasonal sales tax” he had been teasing is, in reality, a year-round sales tax that escalates from 2% to 4% during the summer tourism months. It would also put the state in the driver’s seat of all local sales taxes, requiring all such taxes to flow through the state’s to-be-created sales tax system while also letting the state decide what can and cannot be exempted from all sales taxes.

Notably, the governor’s sales tax proposal – which is modeled on South Dakota’s system, a favorite of anti-tax think tanks – doesn’t include any exemptions for groceries, meaning the tax will fall particularly hard on residents of high-cost communities, where milk and other essentials can be three or four times as expensive as in urban areas.

“All who benefit from Alaska’s public services – residents, workers, and visitors – will share in supporting those services,” Dunleavy wrote in a letter to legislators.

Well, except the corporations.

While Dunleavy’s fiscal plan – which also includes putting the PFD in the constitution, slightly and temporarily raising oil taxes, a 1% spending cap and agency sunsets – is ostensibly meant to bridge the state’s finances from now until major revenue-generating oil and gas projects come online in the early 2030s, it’s also seeking to completely eliminate the state’s corporate income tax.

Eliminating the corporate income tax would wipe out more than $540 million in annual revenue from corporations and large oil companies (many small businesses operate under the personal income tax system and are thus not subject to the state’s corporate tax rate), while the sales tax would be expected to peak at more than $800 million. And it’s also designed so corporate income taxes would phase out two years before the sales tax would go offline, teeing up a couple of years in which Alaskans would effectively be subsidizing corporate income tax cuts.

As Anchorage Democratic Sen. Bill Wielechowski told the Anchorage Daily News, the initial assessment of Dunleavy’s plan is that it’s “very light on taxing people at the top, and very heavy on taxing the poor and working class.”

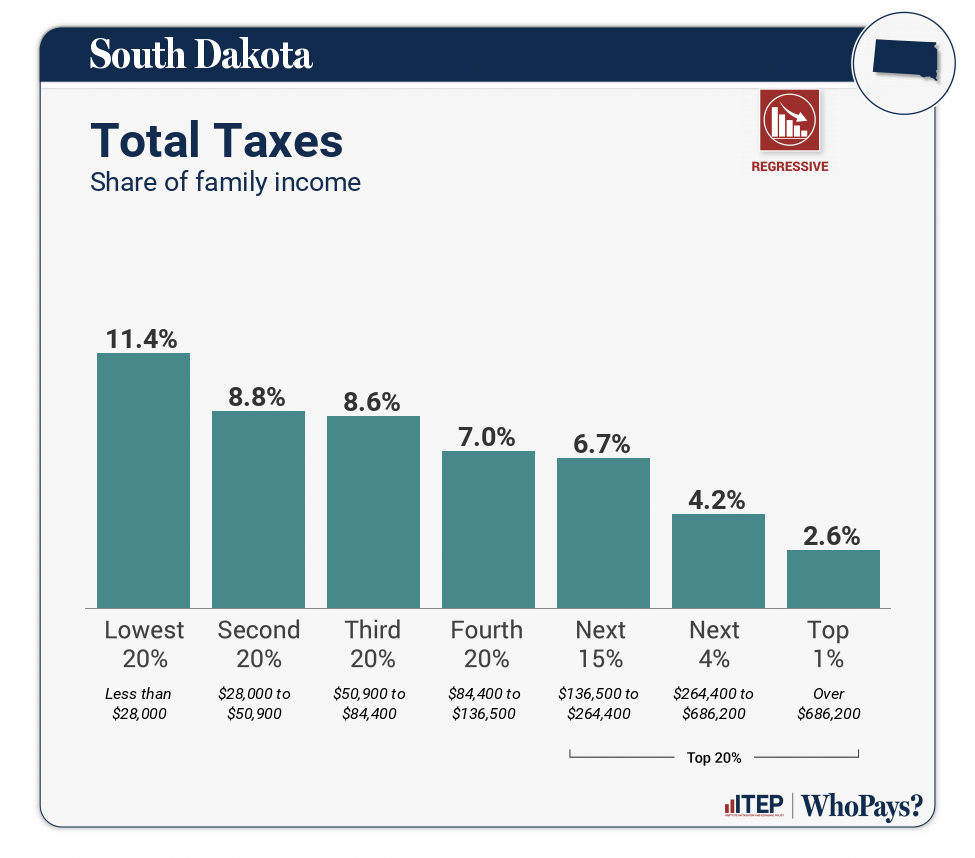

While legislators have not meaningfully advanced a broad-based tax in recent years (why do it when the governor’s going to veto it anyway?), they have had pockets of discussion here and there about the pros and cons of different tax systems. The sales tax generally got low marks because it’s seen as a less equitable way to generate revenue (though, to be fair, it’s more equitable than PFD cuts if you’re part of the “PFD cuts are taxes” crowd), with a daunting and costly road to implementation. Unlike a progressive-rate income tax, a sales tax falls more heavily on lower- and middle-income families, who spend a greater share of their income on goods subject to a sales tax, than on the wealthy.

That’s what has happened in South Dakota, the basis for the governor’s plan.

According to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, South Dakota’s tax burden falls heavily on lower-income residents, earning it the title of the sixth-most regressive tax structure in the country and a place in the heart of corporate conservative think tanks. It’s a system that has made South Dakota a darling of the Top 1% – who pay about 2.6% of their income through the state's sales taxes – while the poorest families shell out over 11%.

The group's outline of what makes South Dakota's system particularly regressive reads a lot like a summary of Dunleavy's legislation: No corporate income tax, no personal income tax and a state sales tax that includes groceries.

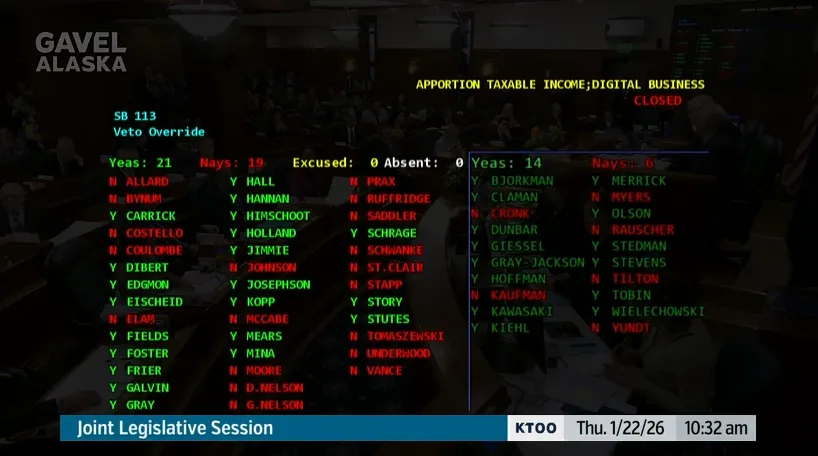

That's going to make it a tough sell, especially when the whole thing also relies on legislators sending a constitutional amendment dedicating 50% of the Alaska Permanent Fund's spendable income on dividend payouts (bringing them to about $3,200 versus the $3,600 in statute or the $1,000 that was actually paid last year). That takes a two-thirds vote in both chambers.

And setting aside the matters of equity, the cost to create and operate a statewide sales tax system that reaches every corner and cash register of the state has also been a major factor in past discussions. According to the governor’s fiscal note, they think they’ll need 67 new permanent full-time employees to operate the sales tax system – a number they reached by taking the spending on South Dakota’s staffing rates and adjusting it based solely on the state’s population (overlooking the fact that Alaska has about nine times the area of South Dakota) – and a $10 million upfront investment. And that's not factoring in the costs to businesses to get into compliance with the sales tax system or changes in spending behavior. The state also proposes a several-year rollout and corresponding education efforts.

All for a tax that's supposedly only going to last for seven years.

Those costs and investments may ultimately prove to be hard to unwind once they’re up and running, especially if the governor’s prognostications for future oil and gas revenue, which also banks on the AKLNG gasline project being successful, don’t pan out for a whole litany of factors well beyond the control of Alaska.

As Dunleavy so convincingly said of his fiscal plan during the State of the State: “The numbers and elements of the plan could work.”

And if it doesn’t, he’ll be long gone by the time the bill comes due.

Stay tuned.

More coverage: Alaska Beacon, ADN, Alaska Public, Dermot Cole

Reading list

The Alaska Memo Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.