Looming school closures expose the reality of a 'balanced budget'

And as if to put a fine point on the reality of budget cuts, a slate of proposed school closures stands to impact low-income families more than others.

Happy Alaska Day, Alaska!

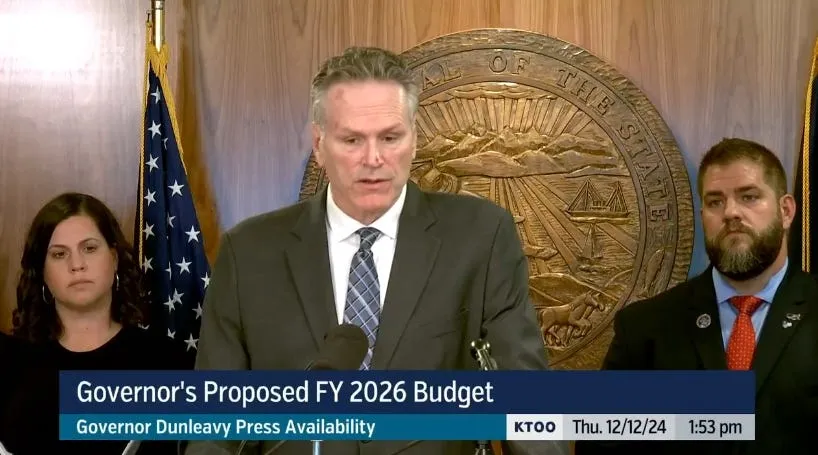

In this edition: This year’s state budget process yielded cheery declarations that after many years of cuts, Gov. Mike Dunleavy and the Legislature finally found a way to pass a “balanced budget.” Never mind the state was relying on a trifecta of booming oil prices, robust financial returns and a healthy injection of federal covid-19 dollars but start to look around and you’ll find that a “balanced budget” for the state can still leave a lot of holes, like the $68 million shortfall the Anchorage School District and its families are grappling with. Today, the district announced six schools and, as if to put a fine point on the impact of the budget cuts, five of those are Title I schools.

Coming up next time (and the time after that): The latest on the APOC complaint against Dunleavy and company, campaign finance disclosures and forum quotes.

Don’t miss: Debate for the State at 7 p.m. on Wednesday. It’s the penultimate gubernatorial forum that should include all four candidates.

The reality of a ‘balanced budget’

Earlier this year, Gov. Mike Dunleavy and the Alaska Legislature were treated to headlines about how they finally figured out a way to balance the budget. Reading the headlines, you might’ve been led to believe that Alaska’s financial situation had turned a corner and we were back on the path to lavish capital budget spending and whopper PFDs. But, as pretty much anyone who’s familiar with the budget would tell you, it was built on a house of strong financial returns, a windfall of covid-19 relief money and booming oil prices courtesy Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

Alone, it was a precarious situation where any big shift downwards in oil prices would throw the state right back into a deficit that, depending on its size, could leave legislators few options other than dipping into the Alaska Permanent Fund’s earnings reserve account. Time will tell how that gamble plays out.

But it’s the other side of the coin that we should talk about today.

The spending.

A “balanced budget” might lead one to believe that the basic needs of the state are being adequately met and that we can maybe catch our breath after nearly a decade of cuts and years of outmigration. But, as pretty much anyone who’s familiar with the budget would tell you, the state’s budget only paints part of the picture and that a lot of the “balancing” that’s been going on in recent years has been to shift the burden over to local governments and local school districts.

Look at what’s happening in Anchorage where the state’s “balanced budget” has left the school district with a $68 million shortfall that’s spurring fears of school closures, program cuts and general doom and gloom. In a letter today, Superintendent Jharrett Bryantt said it’s a combination of enrollment decline (about 20% among young students, which happens to mirror the drop in Anchorage births) and stagnating state funding. Sure, the state approved a $30 increase to the base student funding formula as part of its controversial reading program, but as many legislators pointed out it won’t even keep up with inflation.

Bryantt echoed those legislators’ concerns today, noting that even without the exodus of young Alaskans the school district would still be at the bottom of a big hole.

“The bottom line is when our state government doesn’t increase education funding, it’s cutting education funding,” he said. “An influx of federal COVID-19 relief dollars provided a false sense of security. The reality is our schools are being underfunded and it was never addressed by our state government.”

It’s a situation that districts throughout the state will be likely feeling before too long in some form, if not already. Some areas might choose to raise property taxes while others, like Anchorage, are already up against the state’s limit for local contributions and have few choices but deep system-wide cuts.

Deeper reading, via the ADN: ‘Slow strangulation’: Alaska school districts face fiscal cliff with high inflation and flat funding

The Anchorage School District’s first big-ticket cut was outlined in Bryantt’s letter today: School closures.

Today, the district recommended six elementary schools for closure next year with a final decision expected in December. Previous estimates by the district are each closure of an elementary school saves the district about $500,000. The plan, the district says, would save between $3.4 million and $4 million.

The affected schools include:

- Abbott Loop Elementary

- Birchwood Elementary

- Klatt Elementary

- Nunaka Valley Elementary

- Northwood Elementary

- Wonder Park Elementary

And as if to put a fine point on the reality of budget cuts, these cuts stand to impact low-income families more than others. All but one of the targeted schools are Title I, meaning they have a larger proportion of students who are eligible for free and reduced lunches. Two are in East Anchorage, which drew criticism from East Anchorage assemblymember Forrest Dunbar as putting an outsized burden on low-income families.

“Twice as many schools in East Anchorage as any other part of the Municipality,” he said on Twitter. “Flat-funding from the state is likely going to impact our working class and low-income neighborhoods disproportionately.”

The news about school closures raised alarms for economists who’ve been warning that the state’s exodus of young people and lack of political will to make meaningful investments at home spell trouble for the state’s future.

“Successful states don’t close lots of schools,” wrote Kevin Berry today. “If I was a kid in Alaska, I’d think the state was sending a clear message that my education doesn’t matter.”

The state of schools and the state’s future for young people came up frequently during the Monday gubernatorial forum hosted by the Anchorage Chamber of Commerce. There, both independent former Gov. Bill Walker and Democratic candidate Les Gara called for greater investments in schools and teachers. Walker noted that the state’s annual teacher fair had been cancelled because “Who would want to come to Alaska?”

“We’re building prisons and we’re closing schools. Something’s really wrong with our economy when that’s what we’re doing, he said, later adding. “We are circling the drain on education in Alaska right now. When you shortchange a system for so long, when you kick the can down there for so long, eventually the can kicks back. We’re seeing it. School closures around the state? I’ve not seen that in my lifetime.”

Dunleavy, of course, was not at the forum. Instead, he spent the day announcing his plans to submit a new tough-on-crime bill—which will greatly increase prison sentences for some drug-related crimes—if re-elected.

The Alaska Memo Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.