Republicans are having a weird time with open primaries and ranked-choice voting

Am I so out of touch? No, it's the voters who must be wrong.

It’s Monday, Alaska!

In this edition: Alaska’s primary election is tomorrow, which, under the state’s top-four open primary system, will mean just three of the more than four dozen races up this year will see their fields narrowed. Still, it’s a good opportunity to break down how the races are shaping up, especially with regard to how right-wing Republicans are trying to navigate a system that opened a lane for their mortal enemies: moderate Republicans. With right-wingers hoping to claw back the advantage of partisan primaries, we’ve had accusations of “fake Democrats” and half-hearted pledges to consolidate the fields. Also, I’ll run down those three races where at least one candidate will be sent packing and give an update on an interesting takeaway from the latest round of fundraising numbers.

Current mood: 🌻

Republicans are having a weird time with open primaries and ranked-choice voting

Alaska’s first elections under open primaries and ranked-choice voting in 2022 largely delivered on what its backers had promised: More moderate candidates could run and win in districts that once reliably produced more partisan legislators. And because we’re in a state with more reliably red districts than blue ones, that was mainly seen on the Republican side of the ticket, with voters more often than not opting for the most moderate Republican of the bunch. In the Alaska Legislature, during this last session, we saw that translate to a concerted and bipartisan effort to permanently increase funding for public schools and the most progress we’ve seen on restoring pensions for public employees. Both were ultimately foiled by Republican Gov. Mike Dunleavy and his Republican loyalists, but the progress and the bipartisanship would have been unimaginable just a few years before.

What was particularly interesting is that we had an influx of Republicans who were not only there without party support but were there in spite of it. The semi-closed partisan primaries of the old system no longer played the same gatekeeping role they had, generally producing legislators who seem less fixated on conservative wedge issues and more attentive to actual problems like underfunded schools, understaffed state services and infrastructure. The push for big Permanent Fund dividends, once a central motivating factor for Republicans, seemed to be more blunted by the reality of state budgeting.

But perhaps most critically, the system produced Republican legislators who were less beholden to the party and less likely to fall in line with the governor.

As I wrote before, what’s going to be interesting to see is how those conservative Republicans adapted to the system. Would they look in the mirror and realize that maybe their politics aren’t quite as popular as the partisan primaries made them appear? Or would they blame the system, try to repeal it and launch a bunch of frankly weird efforts to claw back the advantage they once had? If you had guessed the former, I wish I could have been as optimistic as you.

As this election shapes up, we can see now that it’s pretty firmly the latter camp. GOP campaigners have launched an array of efforts to, in the words of one, “circumvent ranked-choice voting” and put partisan Republicans back into office.

On the more out-in-the-open front, we have a handful of pledges for Republicans to consolidate around whatever Conservative Republican gets the most votes in the primary election. The thinking is that a divided field will benefit the Democrats and independents despite that being the whole point of ranked-choice voting. The ranked-choice voting system is there to allow candidates from the same political party to avoid playing spoiler by allowing support to consolidate through the rankings. It’s also not theoretical, as this very thing happened in 2022 when two Republicans made comeback victories thanks to the cross-over support from other candidates.

Republican campaign consultant Trevor Jepsen, who is also the chief of staff for Anchorage Republican Rep. Tom McKay (one of the two Republicans who won thanks to votes consolidating behind him in the ranked-choice voting process), told the Alaska Beacon that the pledges are a way for the GOP to “circumvent ranked choice voting” by essentially treating the primary like a semi-closed partisan primary.

The two legislative races he’s targeting are both in Anchorage, Senate Seat H and House District 9. In Senate H, Jepsen’s boss, Rep. McKay, is running in a three-way race against Democratic Sen. Matt Claman. McKay dropped out of his race for House, which was largely seen as a lost cause after he ran to the right after winning by fewer than ten votes in 2022. Also in the race is Republican former-legislator-turned-perennial-candidate Liz Vazquez. McKay has signed, but Vazquez has not.

In House District 9, which covers Hillside and Girdwood, three Republicans—Lucy Bauer, Brandy Pennington and Lee Ellis—are running against independent Ky Holland. As with Senate H, not everyone has bought into the pledge, and only Bauer and Pennington have signed on. Ellis told the Beacon that he thought it was an “ill-conceived effort” that ignored the fact that most voters in House District 9 seemed to fully understand how ranked-choice voting and open primaries worked.

Republican congressional candidate Nick Begich, who ran against U.S. Rep. Mary Peltola in the 2022 elections, has also signed onto a similar pledge to drop out if he finishes behind Republican Lt. Gov. Nancy Dahlstrom. In a running trend, the Trump-endorsed and party-favored Dahlstrom has not signed on. (I think this race is also particularly interesting because it is a test of the internal struggles of the Alaska Republican Party to unite its disparate factions. Anecdotally, I’ve seen a fair bit of support for Begich, which seems animated by the fact the party does not favor him and might suggest he’s pretty confident he wouldn’t be the one to drop out.)

On the more cloak-and-dagger side, progressives are calling out some Democratic candidates as insincere plants by Republican operatives to muddy the waters and siphon away the Democratic support they believe played into moderates’ 2022 success.

That’d be Lee Hammermeister, who’s running in what is currently a five-way race for Eagle River’s Senate seat, and Tina Wegener, who’s in the four-way race for Kenai’s Senate seat (there’s also perennial fringe candidate Dustin Darden running as a Democrat in Anchorage despite having many positions antithetical to progressives). They’re both in races where moderate labor-friendly Republican incumbents are on the ticket against right-wing Republicans who’ve made things like corporate tax cuts paid for by a sales tax and trans sports bans part of their platform. Flipping the races out of moderate Republicans’ hands (Sen. Kelly Merrick in Eagle River and Sen. Jesse Bjorkman of Nikiski) will be critical if Republicans hope to dismantle the Senate’s bipartisan coalition and replace it with a loyally Republican majority.

Wegener has regularly posted about conservative issues on the Kenai Peninsula, including a post supporting Bjorkman’s 2022 Republican challenger, Tuckerman Babcock. She also posted a picture of her 2022 ballot showing she voted Republican in every race — Dunleavy for governor, Sarah Palin for U.S. House and Kelly Tshibaka for U.S. Senate — even ranking Bjorkman behind an independent candidate.

Hammermeister was listed as a co-host of a fundraiser for extreme-right Republican Rep. Jamie Allard. He’s since told the Beacon that he is a Democrat, supports Harris for president and would join a bipartisan coalition. As for his support of Allard, he claims he didn’t know about her then.

(All subterfuge aside, not knowing about Rep. Jamie “3REICH License Plates Are Totally Fine” Allard might be disqualifying on its own.)

Neither candidate has reported raising or spending a single dollar on their election, which is not helping them beat the allegations.

The thinking, in these cases, is that a Democrat in the general election could siphon away support from the moderate Republicans. However, that’s based on the idea that those moderates only won in the first place because of cross-over Democratic support. That’s something that Anchorage Democratic Rep. Zack Fields — who is running unopposed and has been active in calling out GOP campaigns this year — doubts.

“Do they actually think that they’re tricking people?” he told me in an interview. “I live in Anchorage, so I’ve heard from quite a few people in Eagle River who are fully aware that this Hammermeister guy is a far-right Jamie Allard supporter running as a fake Democrat. I think that in these races, it won’t have much of an impact, and people probably won’t repeat this. It’s not beneficial to be disingenuous with voters.”

In Giessel’s 2022 race, for example, about half of the voters who ranked the Democratic candidate first didn’t rank either Republican. In Eagle River, Merrick’s 2022 race was just between her and Republican Rep. Ken McCarty, and she won with a whopping 58% of the vote. Bjorkman also handily beat Babcock. In all three cases, the moderates won the first round with a plurality.

Why it matters

In the big picture, what we’re seeing is tension between the top-down, party-driven politics that benefitted from the partisan primaries and the new system that explicitly removes the party advantage from it. For independents, moderate Republicans and Democrats, that’s been a good thing. It’s meant that the Legislature has been less motivated by elections — we saw several bills authored by House Democrats pass this Legislature, which was also a rare feat just a decade ago — and has seen more nods to bipartisanship.

For conservative party-focused Republicans, it’s not been so great. The 2023 session brought several stinging blows to the governor and his allies, particularly on issues like education funding. The landmark education bill that the governor vetoed—and legislators like Rep. Tom McKay sank their election chances with—only made it to his desk in the first because he lacked firm control over the process. Moderate GOP legislators, like Sen. Bjorkman, voiced deep concerns with the governor’s policy proposals and weren’t shy about hiding it.

They aren’t playing nice, and that’s a problem.

This quote from former Republican Rep. Sharon Jackson, who is among the three Republicans trying to beat moderate Sen. Merrick in Eagle River, sums up the situation very well: “The difference between Kelly Merrick and I is I am loyal to the principles of the party. I am loyal to the people that depend on my conservative votes.”

The Alaska Memo by Matt Buxton is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Fundraising by the numbers

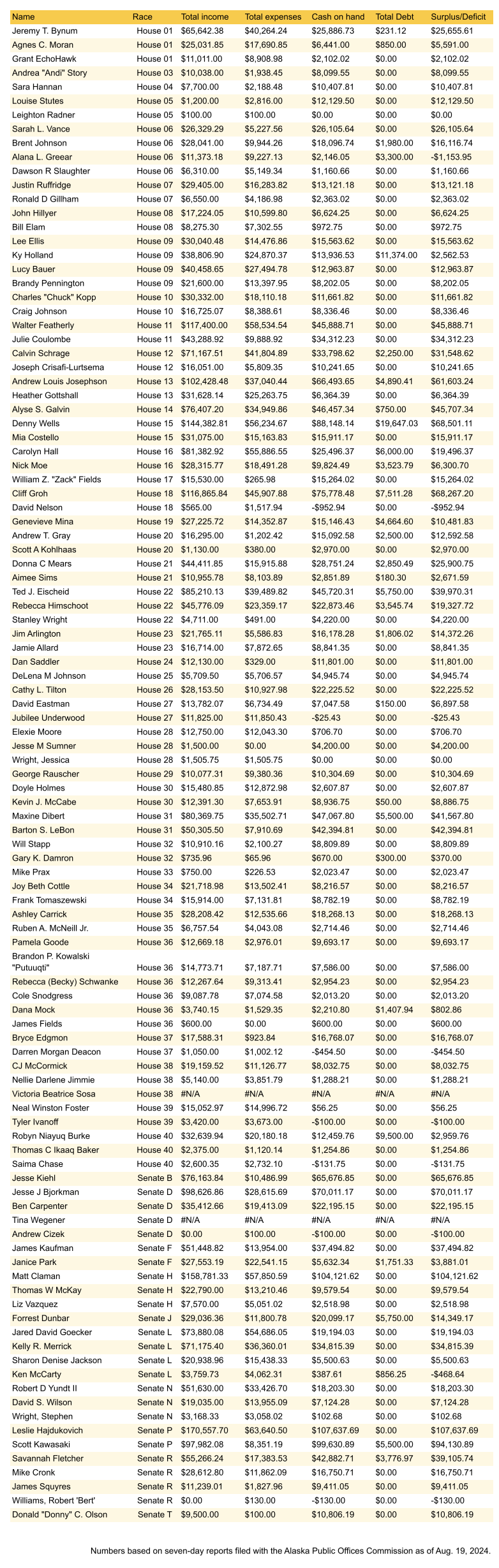

As I noted in a previous edition, the progressive and moderate candidates are generally outpacing their conservative opponents when it comes to fundraising. Sometimes, it’s by unthinkably huge margins, as is the case in the race for East Anchorage’s House District 18, where Democratic Rep. Cliff Groh has raised $116,865.84 to Republican challenger David Nelson’s $565. There are several other races, mostly focused in Anchorage, where the Democratic, independent and moderate Republican candidates are far outpacing their opponents.

What’s interesting about it, however, is the unusual spending by the Americans for Prosperity Alaska—the local wing of the Koch Brothers-backed conservative political network. The group has spent more than all other independent expenditure groups combined, with more than $100,000 reported so far. While that’s not, by itself, particularly notable, the type of spending is interesting. According to the financial reports, a vast amount of that spending has gone to Canvass America, a firm that directly hires people to go door-to-door campaigning on behalf of candidates.

Several politicos I’ve talked with said this is weird and gives the impression that the independent expenditure group is doing the sort of on-the-ground work that a candidate would normally directly undertake with volunteers, letting the candidates essentially sit back with lackluster campaigning. We saw this happen when an independent expenditure campaign did most of the campaign work in Gov. Mike Dunleavy’s first run for governor, letting him sit back and avoid debates.

Also worth considering here is the races they’re getting involved in. To me, it speaks to the races that Republicans see as priorities:

- Jared Goecker, the party-preferred far-right Republican running in Eagle River against Sen. Kelly Merrick – $30,282.38, of which $14,000 is for canvassing

- Stanley Wright, a freshman Republican representative who is in a rematch of his narrow victory over Democrat Ted Eischeid in 2022 – $26,121.96, of which $20,520 is for canvassing

- Mia Costello, a former GOP legislator who stepped into the West Anchorage House race after Rep. Tom McKay dropped out rather than face Democrat Denny Wells in a rematch of his narrow 2022 victory – $20,782.50, of which $18,000 is for canvassing

- Leslie Hajdukovich, who is the Republicans’ latest candidate to go up against 18-year incumbent Fairbanks Democratic Sen. Scott Kawasaki – $18,172.00, of which $14,000 is for canvassing

- David Nelson, a former Republican representative who lost handily to Democratic Rep. Cliff Groh in 2022 – $7,987.06, of which $3,600 is for canvassing

- Jeremy Bynum, the perennial Republican candidate who’s going after the seat held by retiring Ketchikan independent Rep. Dan Ortiz – $500, where none went to canvassing.

While moderates and progressives have outpaced nearly everyone across the board, Republicans have some bright spots in the numbers. Leslie Hajdukovich is the top overall fundraiser in the race against Fairbanks Democratic Sen. Scott Kawasaki, who has fended off loads of well-funded Republicans during his 18 years in office. Jared Goecker is also very slightly ahead of Sen. Kelly Merrick in terms of fundraising, but Merrick has pretty much pulled even in the latest reports. In Ketchikan, Republican Jeremy Bynum has also reported more income than his two independent challengers—Agnes Moran and Grant EchoHawk—combined in the race to replace independent Rep. Dan Ortiz.

I’ve put everything into a chart if you’re interested in the report’s topline numbers. Unfortunately, Substack doesn’t have an easy table feature, so it’s just images. You can find a PDF version here. Dig through the reports on your own here.

Stay tuned.

The Alaska Memo by Matt Buxton is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The Alaska Memo Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.