The Alaska Disconnect

Ultimately, as the report outlines, the question of “who pays” is not just about Alaskans versus non-residents, but poor and middle-class Alaskans versus ultra-wealthy Alaskans.

In this edition: With what little enthusiasm there was for Gov. Mike Dunleavy's scattershot fiscal plan already evaporating, a new report dives into the nuances of different budget-balancing tactics and how they impact jobs and household income. It also provides some much-needed insight on who pays – or doesn't – under the various options, while also giving us a troubling dose of reality over the structural problems created by the Alaska Disconnect. Also, the reading list.

Current mood: 🤼

The Alaska Disconnect

The Alaska Institute of Social and Economic Research released an updated report last week examining options to balance the state’s structural budget deficit and weighing their impact on jobs, the economy and household income. The report was funded by the Dunleavy administration, though there's no indication that he tampered with it (this time). The analysis is presented as a menu of options that doesn't delve into the nitty-gritty of how each source of budget balancing would work – cuts are unspecified, and oil revenue is documented as a flat increase in government take rather than trying to get into the granularity of per-barrel credits and minimum floors – but it provides some much-needed insight into how efforts to balance the budget are spread out across residency and, critically, household income level.

For the “PFD cuts are taxes” crowd, the report will be good news because, once again, it finds that PFD cuts are the most regressive way to balance the state’s budget – that ought to be expected when the PFD is the only source of income for some Alaskans. Cutting to a balanced budget – on top of the nearly 17% cut since oil revenue collapsed in 2015 – would result in the largest total loss of jobs at about 1,000 fewer jobs for every $100 million in deficit reduction. Meanwhile, the least impactful revenue options in terms of short-term job losses are those targeting oil and corporations, with job losses ranging from about 40 to 140 people per $100 million in revenue. If you’re looking to spread the burden of funding state services to non-residents, then a sales tax with exemptions for groceries and other essentials isn’t the worst route.

Doing nothing, as the state has largely done under Gov. Mike Dunleavy, isn’t a great path either, as the constant uncertainty and instability have shrunk the state’s gross domestic product by an estimated 2-3% over the last decade.

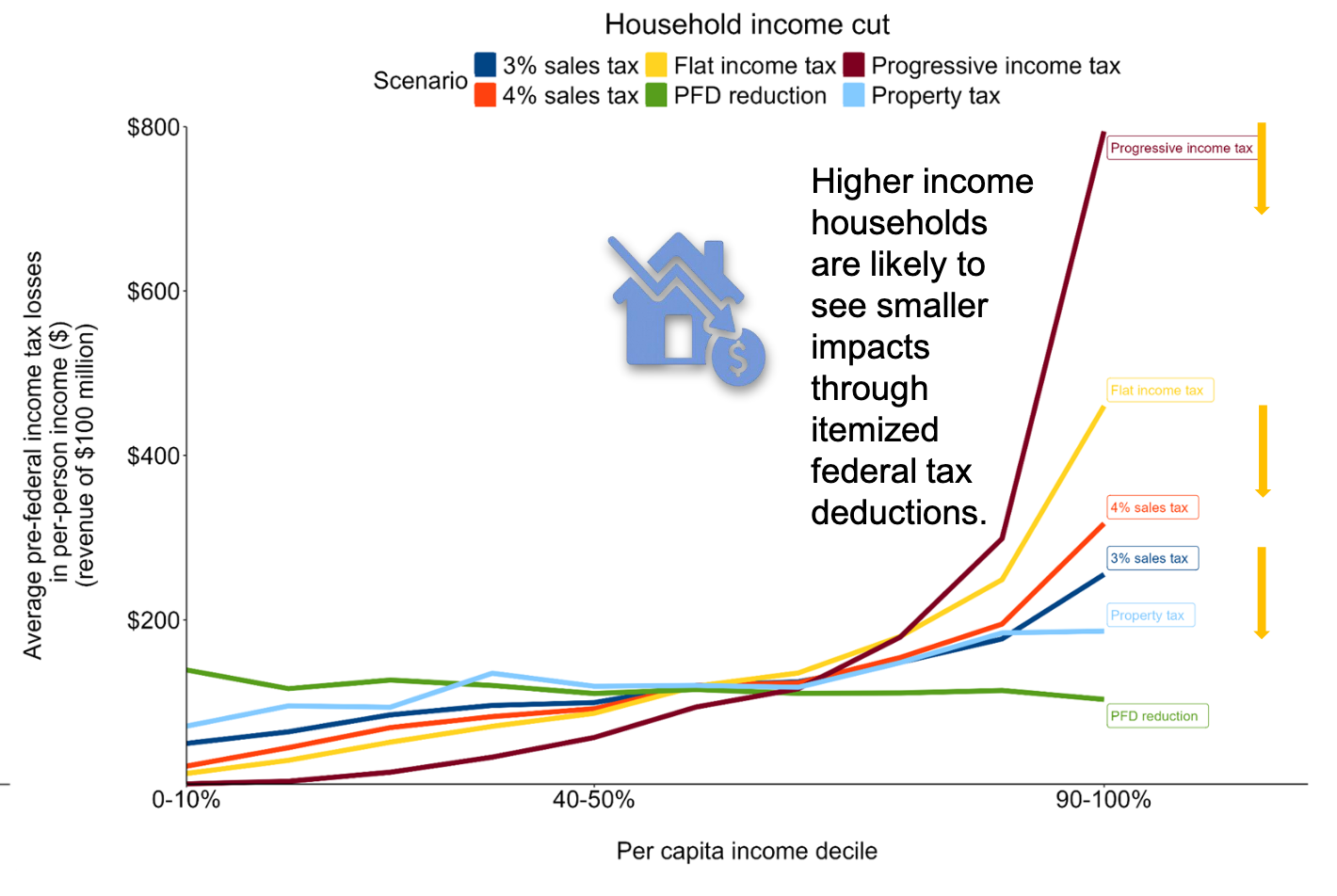

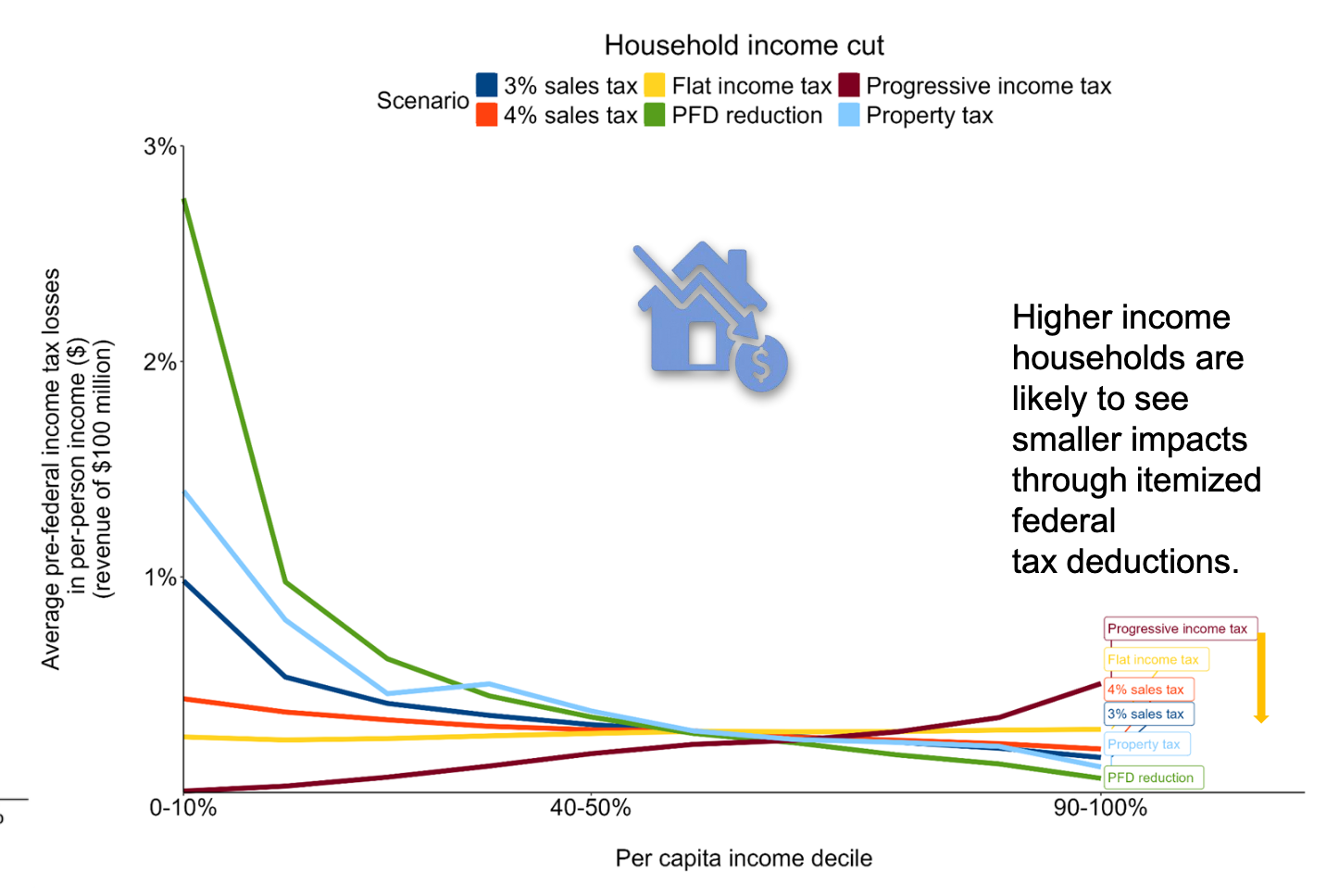

There are a lot of interesting numbers to dig through, but I want to highlight two charts that compare the impact on household income in raw dollars and as a percentage of household income, because I think they illustrate why reaching agreement on broad-based revenue has been so difficult.

In raw dollars, all but the wealthiest of households would see per-household income losses of less than about $150 for every $100 million in state revenue due to PFD cuts or sales, income or property taxes. The very wealthiest households would lose the most under any revenue option other than PFD cuts, largely because they have the most total dollars.

Framing it in terms of the percentage of household income lost to various revenue sources makes it clear that lower-income households are hit particularly hard by PFD cuts, and to a significant but lesser degree by sales and property taxes. Even the most severe-looking per-dollar tax option for the wealthiest households, the progressive income tax, would still take less than 1% per $100 million raised.

As the report puts it: "The wealthiest households would pay five to fourteen times as much in sales taxes as the poorest — but the poorest would lose more as a percentage of their income, particularly under a broader-based tax.

"The income tax options would cost the wealthiest households 35 to 2,000 times as much in dollars as the poorest. These are the only options that would cost the wealthiest households a higher percentage of their incomes."

Ultimately, as the report outlines, the question of “who pays” is not just about Alaskans versus non-residents, but poor and middle-class Alaskans versus ultra-wealthy Alaskans. It’s in that context that it’s important to remember that the biggest beneficiaries from the creation of the Alaska Permanent Fund aren’t the recipients of the dividend, but the wealthy Alaskans who saw an order of magnitude greater benefit from the elimination of the state’s personal income tax.

That’s why, in large part, we have seen a reluctance from legislators – who, along with their deep-pocketed backers, tend to be on the wealthier side of things – to implement any broad-based taxes in service of maintaining the PFD and state services, let alone a progressive one like an income tax. It’s not a particularly vocal group, but legislators across the political spectrum have a philosophical problem with standing up a tax to pay a dividend and see axing the PFD as the easiest way to balance the state’s budget.

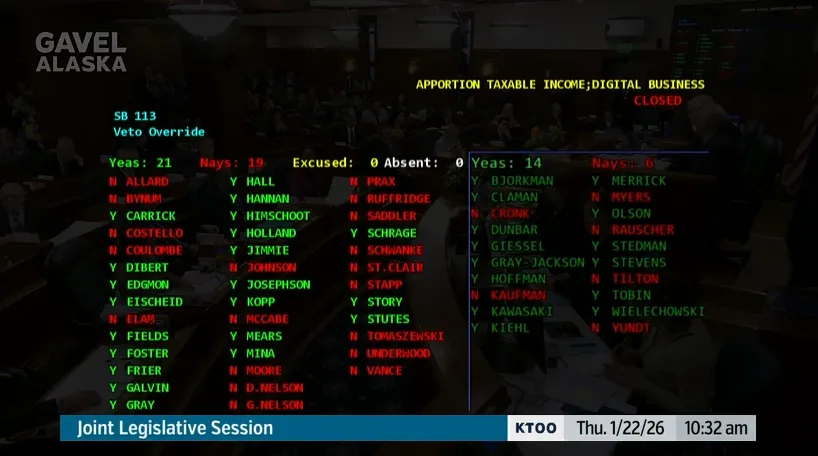

It's a reality that Sen. Bill Wielechowski, an Anchorage Democrat who has supported a larger PFD (and brought a lawsuit seeking one), hinted at during last week's news conference. He noted the governor's omnibus tax bill – which takes a scattershot approach with a large PFD (not regressive), an exemption-free sales tax (very regressive), oil tax tweaks (not regressive), the complete elimination of corporate income taxes (regressive) and the hope that large-scale oil and gas projects pan out (wishful) – is predicated on getting a constitutional amendment guaranteeing a PFD to voters. That requires a two-thirds vote in each chamber.

“As I sit here, I'm not even sure there's 50% approval for anything on the PFD. You've got some people who support a much higher PFD. You've got some people who support no PFD. So I don't think there is support for anything of that nature, constitutionally, on the dividend," he said. "I just don't think the support is there.”

Which, reading between the lines, would suggest that you shouldn't hold your breath on the governor's omnibus fiscal policy bill becoming law this year.

Still, the PFD lever is the easiest, both politically and mechanically, for legislators to turn when they face the immediate question of balancing the budget.

New revenue requires legislation to make it all the way through the process, a position that Dunleavy and aligned Republicans have made a point of opposing. And cuts, at least the type that would actually balance the budget, have been in short supply after a decade of deep cuts and Dunleavy's retreat on cuts after the near-successful recall effort. Already, we've heard some passing suggestions around the Finance Committee tables that the PFD could be on the chopping block if the budget problems Dunleavy created with his vetoes – namely the multi-hundred-million deficit in the current year – aren't neatly resolved.

And setting aside the interminable battle over the PFD, the other big takeaway from the presentation is what lead author and ISER economist Brett Watson told legislators last week is the "Alaska Disconnect," per the Alaska Beacon's coverage. It's the fact that the state has no broad-based tax that links broad economic growth to funding services. The disconnect, put in simple terms, means that economic growth – the kind that brings in new residents, putting new demand on everything from schools to local infrastructure – is bad for the state's budget.

“It would be absolutely catastrophic from the standpoint of the state of Alaska budget,” he said of a hypothetical effort to relocate 100,000 tech industry workers to Alaska. “There would be 100,000 new Permanent Fund dividends to pay, the children of 100,000 new employees to educate, more roads to maintain, more state services to provide, without any additional revenue collected for any of those individuals. And so there’s this disconnect now that’s growing between our private sector economy and what goes on in our public sector.”

So, hey, there's something else to be worried about.

Stay tuned.

Reading list

The Alaska Memo Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.